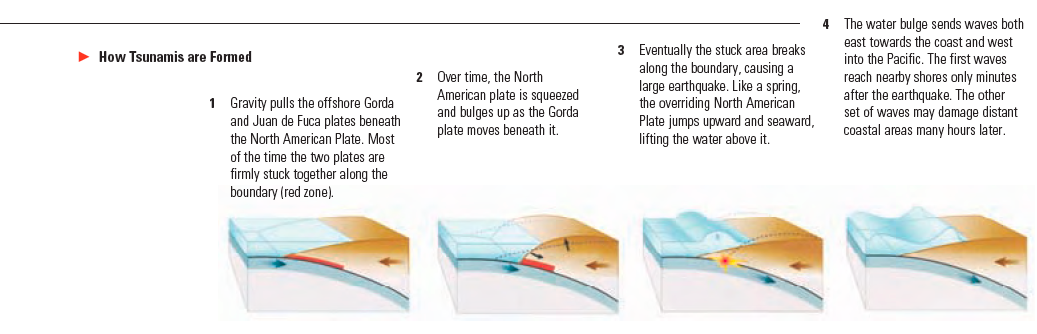

Tsunami Hazards

A tsunami is a series of waves or surges most commonly caused by an earthquake beneath the sea floor. Tsunamis can cause great loss of life and property damage in coastal areas. Very large tsunamis can cause damage to coastal regions thousands of miles away from the earthquake that caused them.

- Beaches, lagoons, bays, estuaries, tidal flats and river mouths are the most dangerous places to be. It is rare for a tsunami to penetrate more than a mile inland.

- Tsunami waves are unlike normal coastal waves. Tsunamis are more like a river in flood or a sloping mountain of water. Tsunamis cannot be surfed. They have no face for a surfboard to dig into and are usually filled with debris.

- Large tsunamis may reach heights of twenty to fifty feet along the coast and even higher in a few locales. The first tsunami surge is not the highest and the largest surge may occur hours after the first wave. It is not possible to predict how many surges or how much time will elapse between waves for a particular tsunami.

- The entire California Coast is vulnerable to tsunamis. The tsunami generated by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake off the coast of Japan caused damage to harbors and ports all along California’s coast. A dozen people were killed in California following the 1964 Alaska earthquake. Tsunamis from local sources are also possible.

When should I evacuate?

Evacuation should not be automatic. Before evacuating you should determine if you are in a hazard zone and consider possible hazards that may exist along your evacuation route. Visit

www.tsunami.ca.gov to find out if you live, work, or play in a tsunami hazard zone.

COUNT how long the earthquake lasts. If you feel more than 20 seconds of very strong ground shaking and are in a tsunami hazard zone, evacuate as soon as it is safe to do so. If you are on the beach or in a harbor and feel an earthquake – no matter how small – immediately move inland or to high ground.

GO ON FOOT. Roads and bridges may be damaged. Avoid downed power lines. If evacuation is impossible, go to the third or higher floor of a sturdy building or climb a tree. This should only be used as a last resort.

If you hear that a tsunami warning has been issued but did not feel an earthquake, get more information. Listen to the radio, television or other information sources and follow the instructions of emergency personnel.

If you are outside of a tsunami hazard zone, take no action. You are safer staying where you are.

There are two ways to find out if a tsunami may be coming. These natural and official warnings are equally important. Respond to whichever comes first.

Natural warning. Strong ground shaking, a loud ocean roar, or the water receding unusually far exposing the sea floor are all nature’s warnings that a tsunami may be coming. If you observe any of these warning signs, immediately go to higher ground or inland. A tsunami may arrive within minutes and may last for eight hours or longer. Stay away from coastal areas until officials announce that it safe to return.

Official warning. You may hear that a Tsunami Warning has been issued. Tsunami warnings might come via radio, television, telephone, text message, door-to-door contact by emergency responders, NOAA weather radios, or in some cases by outdoor sirens. Move away from the beach and seek more information on local radio or television stations. Follow the directions of emergency personnel who may request you to evacuate beaches and low-lying coastal areas. Use your phone only for life-threatening emergencies.

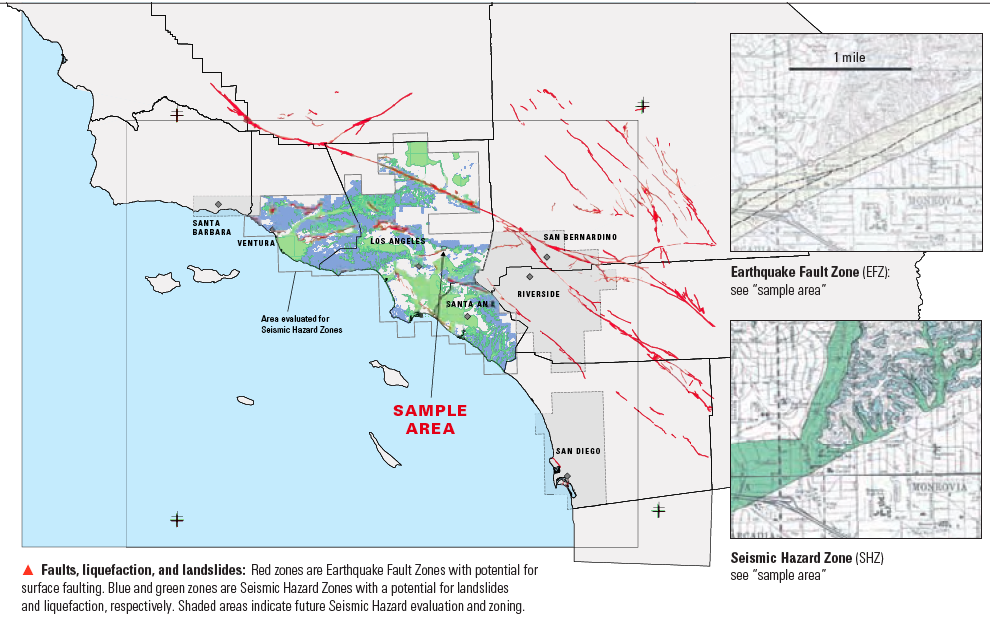

Larger imageFaults, liquefaction, and landslides: Red zones are Earthquake Fault Zones with potential for surface faulting. Blue and green zones are Seismic Hazard Zones with a potential for landslides and liquefaction, respectively. Shaded areas indicate future Seismic Hazard evaluation and zoning.

OTHER HAZARDS

In addition to strong shaking during earthquakes and the potential for tsunamis along the coast, there are location-specific hazards that can cause additional damage: surface rupture, liquifaction, and landslides. The California Geological Survey produces maps that identify Earthquake Fault Zones and Seismic Hazard Zones where these hazards may occur. State laws require that every person starting to “put down roots” by buying a home or real property in California be told if the property is in one of these zones. You can also visit myhazards.caloes.ca.gov/ which has an interactive map for learning about the hazards where you live or work.

Seismic Hazard Zones (SHZs) identify areas that may be prone to liquefaction or landsliding triggered by earthquake shaking. Liquefaction is a temporary loss of strength in the ground that can occur when certain water saturated soils are shaken during a strong earthquake. When this occurs buildings can settle, tilt, or shift. Landsliding can occur during an earthquake where shaking reduces the strength of the slope. These hazards can usually be reduced or eliminated through established engineering methods. The law requires that property being developed within these zones be evaluated to determine if a hazard exists at the site. If so, necessary design changes must be made before a permit is granted for residential construction. Being in an SHZ does not mean that all structures in the zone are in danger. The hazard may not exist on each property or may have been mitigated. Mapping new SHZs in urban and urbanizing areas is ongoing statewide. Current zones, as established by the California Geological Survey, are indexed at www.conservation.ca.gov/cgs.

Earthquake Fault Zones (EFZs) recognize the hazard of surface rupture that might occur during an earthquake where an active fault meets the earth’s surface. Few structures can withstand fault rupture directly under their foundations. The law requires that within an EFZ most structures must be set back a safe distance from identified active faults. The necessary setback is established through geologic studies of the building site. EFZs are narrow strips along the known active surface faults wherein these studies are required prior to development. Being located in an EFZ does not necessarily mean that a building is on a fault. Most of the important known faults in California have been evaluated and zoned, and modifications and additions to these zones continue as we learn more.